Rewrites and Refactors

Note: I am not sure I believe what I wrote here, there’s a lot of great arguments for doing things in other ways. Personally, I have not refactored the city generator I wrote, and these days, I believe that if I start that project again, I would completely throw away the code I wrote.

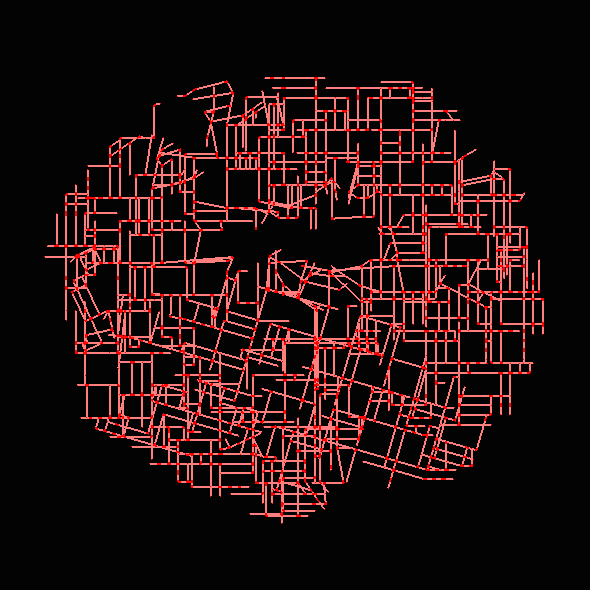

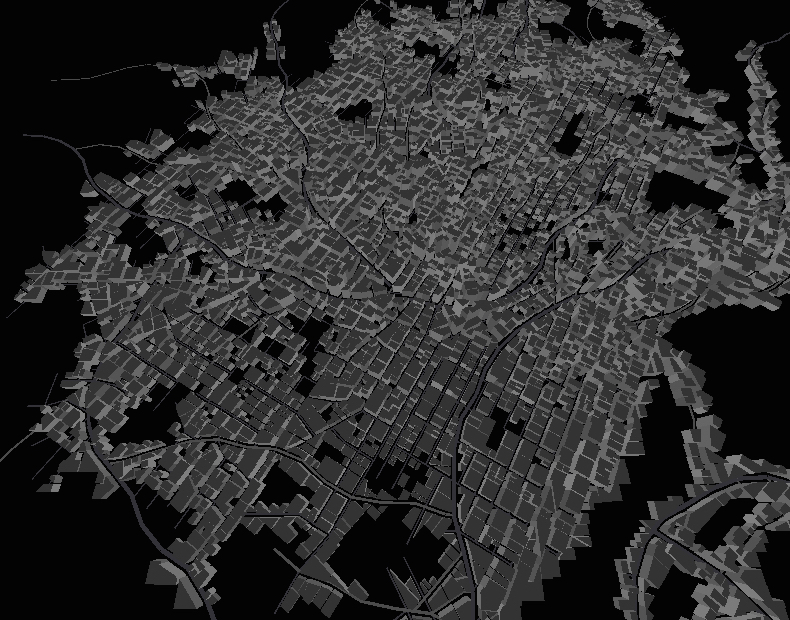

I’ve started to read Refactoring by Martin Fowler, and it’s inspiring. The book starts out with an example of a small project that has theoretically overgrown its original implementation and must be refactored. The thing is, I’ve got a project that is in the same state. My Java City Generator, cleverly named “citygen”, was written in a time where I really didn’t understand programming, much less OOP or version control.

The code is ugly, it has commented out code blocks everywhere, it’s barely documented, and is mostly procedural. It looks and feels a lot like legacy code that I’ve had the opportunity to work on.

And it’s my third try. Over the past four years, I’ve thrown out everything in hopes that – this time – this time I’ll do it right.

I had the thought that every programmer has sometime in their career:

“Holy hell, this code is awful.”

which leads to

“I should just rewrite it.”

Rewrite heaven.

This has worked pretty well for me so far. The citygen repository you see today is a complete rewrite of an older city generator I wrote. And that city generator was in turn a rewrite of another city generator I wrote.

It was when I started realizing that my second generation of city generator was starting to cause me immense pain that I decided to trash it all, and start writing the third generation. What a good idea! In a few weeks time, I had the functionality of the second generator without the bugs, and it was beautiful. And then I started developing features, and with features comes complexity, and with complexity comes ugliness.

Then I think college applications were a thing. The next time I touched the project was at the beginning of 2014, when I created a new repository and said to myself, “I’m going to do this right this time.” I quickly forgot about the project, and didn’t think about it until a few days ago when I picked up “Refactoring”.

I live in a land of unicorns and happiness.

My city generator is a sandbox, it’s all mine, and I can do whatever I want with it and no one can tell me not to. I have no customers or clients, and I don’t need to worry about breaking outward-facing APIs or making anyone mad, which is exactly why I chose to rewrite it three times. Whenever I felt that my velocity was impeded by my code, I abandoned it.

The sad truth.

Rewrites can fail, and they do, and everyone is scared of them. Management hates rewrites, and they have reason to do so. Rewrites are bad and kill companies. The bigger a project gets, the more the programmers working on it will hate it, and the more push there will be to convince management to dedicate time to rewriting it. And managment has been trained to say “no” because they’ve learned that the company has survived this long without anything disasterous happening, and therefore the developers are full of shit, and should just continue developing features.

Rewrites are easy, and refactors are hard.

Rewriting code is the easiest decision to make. You immediately feel relieved that you aren’t working on that crap that you just wrote, because you’re smarter now! You know how to write maintainable code! You’re going to do it the right way now! You know how to lie to yourself!

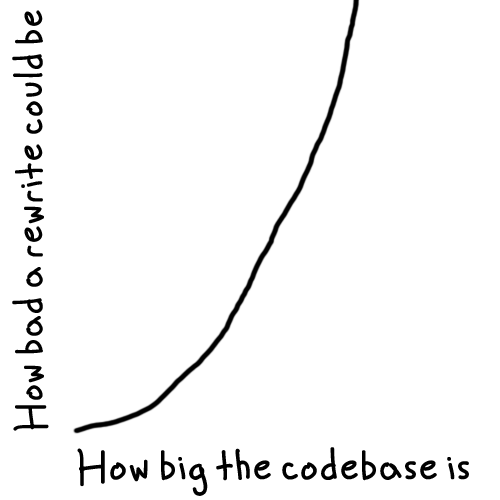

Rewriting code is often the worst decision to make. The scale of how bad that decision is lines up pretty well with the magnitude of the codebase.

Additionally, the urge to rewrite code lines up pretty well with the size of the codebase. This is the natural progression of a codebase. This is why monoliths are broken up into parts. This is why you refactor.

It’s time for me (and you) to learn how to refactor.

I find myself trying to do too many things all the time. That’s how my brain works, by default, I jump from topic to topic and find myself working on everything at once and therefore nothing.

I’m trying to condition myself though, trying to work on one thing at a time. I’m being more careful with my commits, attempting to solve one issue at a time, instead of everything that I see. I think a number of programmers have the same problems I have, and I think that this failure to discipline oneself is why rewrites don’t work.

Rewrites fail because the point of them is to change everything: behavior, implementation, language, etc. The wide scope of a rewrite is inherently wrong, because humans flounder when there’s too much to be done.

In a refactor, the programmer has one task at a time; changing one part of an application without affecting the overall behavior. If the developer does the process correctly, the program will operate in the exact same way. That’s rather unexciting, which is why it’s so hard for us.

Code tends to become unmaintainable in the same iterative development that a refactor needs to be to work. Developers are lazy, and shortest-path is attractive, especially in a startup culture. But all startups (and developers) eventually face code that must be fixed, that prevents velocity, that is scary, that causes burnouts. The hard part fixing it without killing the project.

TL;DR: I have no idea what I’m talking about.

Caveats

I mainly wrote this to convince myself, and that means that I’m not sure about what I’m saying. Every situation we find ourselves in requires a different solution, and the situation I’m in is a very difficult one. When I posted this, I got a comment that puts my post into perspective:

I’ve found “rewrite vs refactor” to be a false dichotomy. The arguments tend to define rewrites as being from scratch with functional changes and refactors to be a long series of very small no-op changes to existing code. In practice a hybrid model is not only quite possible but often ideal. If your application is modular, you can rewrite individual modules from scratch. If it isn’t modular, you can first refactor it to be modular enough and then slowly rewrite. Want to switch languages? Cross compile, SWIG, embedded interpreter/vm, etc, then port things in small pieces. Many applications (particularly web apps) tend to wind up in a tree/dag-like structure. These tend to work well for bottom up (leaves first) “rewrites”. Or start from scratch at the topmost level and re-use all the “legacy” code/components/functions assembled in a different way. There’s rarely a good reason to rewrite an entire application at once, but that in no way precludes you from effectively rewriting it without just the tedium of no-op refactors. It just requires some more thought and strategizing up front.

and

One other thing I’ve learned: when dealing with a hunk of unreadable/undocumented/otherwise-terrible legacy code (a single line, a function, module, class, util, file, whatever) that you consider unfixable and in need of a rewrite, even though it is painful, before you rewrite it, at least refactor it (the slow, tedious, no-op way) a little–enough that you can actually understand exactly how it works. You don’t have to fix it: it is unfixable and you are rewriting it after all. But I’ve found it is nearly always worth the pain of getting into an at least semi-readable state so you know what you’re dealing with.

– both from Christopher Souvey

I find Christopher’s words to ring true. My trouble in this post is trying to justify a single solution when there are infinite. The one constant is that when a problem is understood, both the cause and the effect, the purpose of action is far safer and more effective. The engineering idiom “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is overused, for broken systems are far too often classified as working. When engineers cannot work, a system is broken. Christopher pointed me to Chesterton’s Fence, which I have quoted below:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.